|

MELVIN A. SCHILLING, MUSIC AND SOUND, 1933-2022 2022 January 27 |

|

|

MELVIN A. SCHILLING, MUSIC AND SOUND, 1933-2022 2022 January 27 |

|

We lost

Melvin A. Schilling,

on 2022 January 24.

He was born 1933 April 23 and had

nearly nine decades of satisfying, productive life.

This morning, 2022 January 27,

I just got the news of his passing from his son,

Howard.

I was privileged to be his customer and friend

for forty-four of his eighty-eight years.

(We shared a few Philadelphia Orchestra

concerts too.)

We lost

Melvin A. Schilling,

on 2022 January 24.

He was born 1933 April 23 and had

nearly nine decades of satisfying, productive life.

This morning, 2022 January 27,

I just got the news of his passing from his son,

Howard.

I was privileged to be his customer and friend

for forty-four of his eighty-eight years.

(We shared a few Philadelphia Orchestra

concerts too.)

Mel loved the piano both playing and listening. On his last birthday I mentioned he had eighty-eight years to match eighty-eight keys on his piano. He was perky and joyful when we last talked on 2021 September 10, Friday, and we exchanged emails up until 2022 January 6, three weeks ago. Maybe if he had a Bösendorfer with four extra keys he would have made it to ninety-two.

I owe Mel a real eulogy web page, but this will have to do. I put a bunch of stories at the bottom of this page.

Melvin A. Schilling was "Music And Sound," MAS,

and the Music always came first before the Sound.

Mel was a pioneer in the world of hifi audio,

what we call "high end" audio,

where the commitment to the reproduction of music

and its subtleties is paramount.

He created a world of listening to recorded music

with a keener ear

and what he didn't create himself

was created by people he helped

and people who knew him and respected him.

Melvin A. Schilling was "Music And Sound," MAS,

and the Music always came first before the Sound.

Mel was a pioneer in the world of hifi audio,

what we call "high end" audio,

where the commitment to the reproduction of music

and its subtleties is paramount.

He created a world of listening to recorded music

with a keener ear

and what he didn't create himself

was created by people he helped

and people who knew him and respected him.

I think of Mel every morning with joy.

I don't have a choice, really.

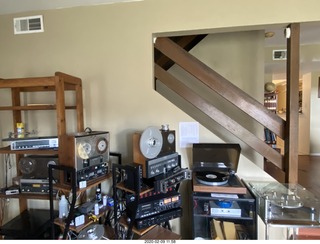

I bought my Linn turntable and my two ReVox tape decks

in his Woodland-Hills store.

He "sold" me his old Quad ESL electrostatic loudspeakers

for a pittance (with the Decca ribbons on top),

they were really a gift from "Uncle Mel,"

and I listen to them every day.

It's hard not to admire somebody who gave me

such a clear window

into concert halls and recording studios

decades ago,

the finest musicians on tape, vinyl, and compact disk (CD).

I think of Mel every morning with joy.

I don't have a choice, really.

I bought my Linn turntable and my two ReVox tape decks

in his Woodland-Hills store.

He "sold" me his old Quad ESL electrostatic loudspeakers

for a pittance (with the Decca ribbons on top),

they were really a gift from "Uncle Mel,"

and I listen to them every day.

It's hard not to admire somebody who gave me

such a clear window

into concert halls and recording studios

decades ago,

the finest musicians on tape, vinyl, and compact disk (CD).

For now I'll leave family and friends with a message I gleaned from Theodor Geisel, one of last century's most wonderful authors. "Don't cry because it's over. Smile because it happened." Mel Schilling, you gave me forty-four years to smile about, forever and always.

When it comes to Mel Schilling's

life,

I feel like I walked in

at the beginning of Act II

and I had to gather what happened in Act I

from the story and a few hushed whispers around me.

Now back to my own Story of Mel.

There was a hifi store in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania,

at 11½ Old York Road close to where

it intersects with Easton Road.

In this part of the play "Mel's Life"

the scene is still in the Philadelphia area

while the main character Mel has headed far away,

out west to California somewhere.

The store is Music And Sound Limited

and the Princeton student with orange hair walked in.

(I had incredibly-bright orange hair in those days.)

This would have been sometime around 1976 Summer,

so let's fix that date to start my part of the story.

The outer room was professional audio gear.

I recall huge mixing boards and not much else about that room.

The inner room was the cool place.

There were gigantic speakers and

expensive-looking hifi components along one wall.

The most-noticeable was a pair of three-panel speakers

set up in a zig-zag and a large amplifier with

two big VU meters

calibrated in decibels (dB).

Along the far wall I remember a top shelf with

five large Crown tape decks

and there was an enormous box-shaped tower.

An imposing gentleman Larry Segelin

treated the orange-haired shabby college student with respect

well beyond what he was likely to buy from this expensive store.

He put on a record Supertramp "Crime of the Century"

on the high-end demo system with the three-panel speakers

and the sound was amazing.

The clarity of the instruments was stunning,

the bass was deep and firm,

and every aspect of the recording was clearly represented

in its place between the speakers.

This was a very different experience than

shopping at Tech Hifi,

the usual college-student hangout.

It was a different world and clearly an expensive world.

They could have

put me down or thrown me out of the store.

(There's no Constitutional edict about

discrimination on the basis of poverty.)

Instead Larry asked me about my college hifi

and he introduced me to high-end audio

by selling me a pair of black-plastic piezoelectric tweeeters

that could go atop my AR-4 bookshelf speakers for $15

and, Wow!, they sounded better.

Fifteen bucks for high-end audio.

It wasn't very high end, but fifteen bucks wasn't a lot of money.

I had built a tonearm out of Lego blocks,

Larry showed me a cool "articulated" tonearm called the

Vestigal

and I built my next tonearm out of

Erector Set and paper clips.

I bought a couple of phono cartridges

to fasten to this new tonearm,

as left-handed as I am so the user saw the back of the cartridge.

Larry sold me a turntable called the Fons,

no relation to the television show "Happy Days."

Larry even gave me the plans for a subwoofer

which my friend Andy built with me.

Larry sold me the speaker-cone driver.

It was a black monolith remniscent of the movie

"2001: A Space Odyssey," I kept it for a few years,

a friend helped me build another one,

and Andy still has the first one we built together.

I designed my own crossover and, Pow!,

I became an audiophile.

There was talk of somebody named Mel Shilling

who used to own the place, but he wasn't around anymore.

When I was a graduate student at Stanford

I found my way to Los Angeles and I stopped in at

Mel's new store Music And Sound of California

in Woodland Hills.

The gentleman who waited on a pathetically-poor student

sold me a Son of Ampzilla amplifier

which was quite a bit better than the Dynakit Stereo 70.

Then Mel introduced himself to me and

gave me the real show in the back room,

two three-panel Magneplanar Tympani speakers,

an Electro Research A75 amplifer,

and a Linn Sondek LP12 turntable.

On a subsequent visit I recall Steely Dan "Aja"

where the little bell on the title-track chorus

that I could just make out on my stereo

was so clear and wonderful and part of the song here.

Mel was a gentleman to me from then

to our last communication a few weeks ago.

He handed me a copy of a record with seven names and seven pictures,

Norman Blake,

Tut Taylor

Sam Bush,

Butch Robins,

Vassar Clements,

David Holland, and

Jethro Burns

on Flying Fish records.

I asked what it was,

all Mel said is, "You'll like it."

Yes, I liked it,

yes, I still have it,

I listened to it as I wrote this section, and,

yes, I still like it.

It was a longer story, little to do with Mel,

how I acquired a little money and was able to get a nicer hifi.

I was back home in Philadelphia in Clay Barclay's store,

in 1980 I think,

and there was a used Electro Research A75 for $1100.

Mel was pissed at Clay for selling his old customer

a set of Crowns to replace his revered A75, a bit of rivalry.

He also warned me the amp was "pot luck,"

there were no guarantees of anything.

It was a financial pinch

but I had the money and I bought the amp,

I put it in the back of my 1973 Volkswagon Superbeetle,

and pulled it out on my first stop on the way back to Stanford,

my friend's house in Pittsburgh.

Sometime in the 1970s Mel teamed up with

John Iverson,

one of those tough, crew-cut military engineers.

They formed a company Electro Research.

The story of the A75 is that it was supposed to have been

an amplifier for moving a turret weapon of some sort

and it was the best-sounding amplifier ever.

(I heard a lot of amplifiers in my audio career and,

as of 1982, only Rappaport AMP1 gave it a contest.)

You can only imagine how excited I was to hear this amp

at my friend's place.

He had a pair of Fried B satellites

(the top part of Fried's Model H

without the subwoofer)

and we hooked up the amp to the tape-output of his receiver,

no volume control and nervous about that,

and we put a record on.

Whee! Holy shit! Wow!

This ugly thing sounded amazing!

Putting on one record after another

we listened for an hour.

Then the amp went silent, nothing, nada, zilch.

We checked and the slow-blow seven-amp power fuse had blown.

Well, my attitude is you replace a fuse once,

try it again, and then give up.

We found a slow-blow seven-amp power fuse at a store,

turned the amp on, and it caught fire.

Flames!

My precious $1100 wonder-amp that had sounded so amazing

was now fuel for its own fire.

My "pot luck" amp had gone to pot.

Oh shit.

Well, I was going through Los Angeles anyway

on my way back to Stanford, so I called Mel.

(Remember Mel? This is a

song

about Mel.)

Two days after our sorrowful, sad conversation,

I dropped the amp off at Music and Sound of California

and Mel said he would give the amp to John Iverson.

Maybe he could fix it.

A little while later

John put the amp on the back of his Harley

and drove it to his factory, then in Amarillo,

where he worked his wonders.

The first thing he fixed was the fan.

Fan?

I didn't know the amp had a fan.

No, you didn't because it wasn't working.

Normally you can hear the fan's faint 300 Hz hum,

but this amp was totally silent in operation.

Once it got too hot, then it just became totally silent.

John brought the newly-repaired A75 back to Mel's store,

I drove down to L.A. and picked it up.

With trepidation I asked the terrible question, "How much?"

Nothing, said John through Mel, it shouldn't have broken.

As much as it hurt at the time,

For the man's serious effort and cost

I coughed up a token $500

which he accepted

(again through Mel,

I only met John a couple years later)

and I took the amp home to my apartment in

Mountain View, California,

where my audio-weenie friends and I spent many hours

enjoying its incredible resolution of

content, texture, timbre, image, and all that audio stuff.

We also enjoyed how much more music there was in the music.

Whee! Holy shit! Wow!

This time there was no fire.

Mel didn't have to do any of this.

At that time he really didn't know me from,

well, you know,

Adam.

That's what kind of person and businessman Mel was

then, before, and since.

Well, I invested about $2500

(with a lot of do-it-yourself patent prose)

in a patent on my articulated

tonearm

inspired by the

Vestigal tonearm Larry had shown me.

Now I wanted to turn it into a business,

so I asked Mel for counsel and advice

when I was in L.A.

Mel comes back,

"I'm busy at the store,

why don't you come by my house later."

I don't think I would have felt more honored

if the Pope invited me to his private quarters

or the Queen invited me to her chambers at Buckingham Palace.

This was Mel Schilling's house.

My next thought was what kind of music system

would have Place of Pride in Mel's living room.

I could only imagine what sort of equipment

I would see there.

I should not have been surprised

at what the pioneer of high-end audio would have

in his living room.

Not a single piece of audio gear,

just a full-sized, nine-foot Steinway grand piano.

Mel talked to me about my prospects

as a high-end manufacturer,

not too good actually.

(In the back room, by the way,

on sagging-cardboard-tubes shelves,

was the best hifi I had ever heard.)

First, Mel gave me a tongue lashing about

doing a second run of LOCI tonearms

when the first hadn't produced sales results.

"You've got all these dealers who have tonearms and haven't paid

and you're paying for a second set."

He said no "audiophile" has ever made money in hifi,

one has to be a businessman.

With the compact disk coming onto the market

turntable and tonearm sales are doing down and,

just to rub salt in the wound,

Linn was coming out with their Ittok tonearm

and their dealers would be under tremendous pressure

to sell that tonearm instead of mine.

When I got my Linn Sondek LP12 turntable

I wanted to learn to set it up myself.

I spent hours and hours trying to adjust the three springs,

height and rotation,

and I couldn't get the turntable to bobble evenly

in all directions of motion.

I brought the turntable into the store

and begged for help.

Mel had the turntable all balanced in less than five minutes.

There was a trick for the Linn:

Adjust the springs so the floating armboard

is exactly the same height as the wooden plinth frame

and centered exactly in the larger, rectangular place for it.

He rubbed his finger across the corners

to feel how level it was.

Once it passed his look and touch test,

the 'table was perfect, even movement in all directions.

He tested it by pushing the spindle down and releasing it

to see if the turntable bobbled vertically with no side motion.

Mel was similarly facile setting up Magneplanar speakers

in a listening room, a minute or two.

It took me hours to set those speakers up when I tried it.

Here's the thing I liked about Mel's understanding of audio.

He wasn't himself an engineer.

Instead he surrounded himself with smart people.

He knew a bunch of shortcuts and he understood

that they were specific shortcuts.

I remember at one hifi show some fellow walked

up to the C.J.Walker turntable and did the same bobble test,

it didn't bobble straight,

and he made disparaging remarks about the suspension.

He was wrong, that test was a great shortcut test

for the Linn, not a general test for all

floating-suspension turntables.

When all the digital-to-analogue systems

seemed to be terribly sensitive to power supplies,

his new company Camelot

came out with a product that used a battery

so there would be no line-voltage variations.

It was called the Arthur with a switch

for "performance" on the batteries and

"rehearsal" for running on the A/C-line wall electricity

while the batteries were charging.

For me high-end hifi was about revelations

about how well machinery could reproduce music and,

as a seriously-wonderful side effect,

about music itself.

After Mel found me an Electro Research EK1

(from a dealer in Wisconsin, I think, who had one

and didn't want to sell it to an actual "customer"

as it was no longer a supported product),

I figured there weren't too many hifi revelations left.

One time when I visited his house

in Huntingdon Valley, Pennsylvania,

he played me the Weathers turntable from 1960.

Its FM technology couldn't do stereophonic reproduction,

a necessity for a high-end hifi product,

so that product went away.

On the Opus 3 hifi-demonstration record

the Swedish woman's voice was so much more real

than my EK1.

I wasn't expecting another holy-shit-it's-better moment.

If I had to give up stereo forever-and-always

to have that sound, I probably would say "no"

because stereo image is such an important part of

my musical experience,

but it would be nice to have both

my current set and the Weathers.

More recently Mel got me products

from his Camelot company,

an amazing compact disk player called the Round Table,

and a digital-to-analogue computer-USB stick called the Magic.

My friend Jeff Polan,

a real engineer in many ways including audio,

gave me some wall-line-electricity filters

that I soldered into plugs from the hardware store,

but I wanted to find somebody who make these filters

into a real product.

(I get nervous playing around with

wall-line voltage that gives more a tingle.)

Mel sent me Camelot Flux Conditioners that are wonderful

and, yes, they sound better than my hobby-soldered filters.

There are stories to tell of dinners at hifi shows

with a table full of his audio business associates

where I was allowed, literally, a seat at the table,

thank you Mel,

meeting some truly interesting people in hifi audio,

thank you again Mel,

and just being part of a scene for

more than four decades,

thank you yet again Mel.

Sometimes I feel I'm not an owner of the wonderful machines

I got from Mel Schilling, but only a caretaker for some

future audiophile.

Our last emails were about his concert programs going back to 1949

and how he was enjoying Spotify on 2022 January 6.

In my next email,

inspired by a "cold" email I got

from an audiophile somewhere far away

asking about John Iverson's "massless, force-field" loudspeakers,

I was going to ask if Mel had ever heard them.

I don't know what I did right

to deserve special friends like Mel.

Maybe I just got incredibly lucky.

I'm thankful to whatever twist of fate

that connected me and him.

18:21:02 Mountain Standard Time

(MST).

30 visits to this web page.